“This is as much a weapon of war as it is a business in my opinion,” Brendon Babenzien says to me. In two and a half hours of talking with Babenzien, who speaks in casually kinetic monologues, he will not give me a tidier summary of his aspirations for his apparel brand Noah.

When Babenzien says this, I can’t help but think of American folk hero Woody Guthrie. Guthrie was a prolific, self-taught songwriter and political polemicist; punk before there was punk (even his revered “This Land is Your Land”, remembered as uncomplicatedly patriotic, was originally written as a critical protest). His music was deliberately simple, a three-chord candyshell to deliver the cutting rawness of his lyrics to the masses. His politics were complicated and slippery, but also depressingly current: he was vocally anti-fascist and anti-Nazi, viewed the corporate capitalist oligarchy as a greedy and corrupting power threatening the world, and thought racial and gender equality crossed with organized labor was the antidote. He even wrote a song condemning a Trump as racist, in this case the President’s father Fred.

For Guthrie, the battle against Hitler and the spreading cloud of fascism was a crescendo in the classic battle between good and evil, and humanity hung in the balance. He sang about it. He wrote heated letters to his unborn daughter about it. And in 1941, as Hitler invaded the Soviets, Guthrie took a guitar he borrowed from friend Will Geer in New York and painted “This Machine Kills Fascists” on its body. It was a meme come 70 years too early.

As a historical figure, Woody Guthrie is a complex tangle of contradicting legends and truths. On the one hand, very few people can match Guthrie’s romanticized impact on America’s identity and culture. On the other, Guthrie was regrettably enamored with his own legend (he titled his autobiography Bound for Glory), an attempted draft dodger, and almost certainly a Communist sympathizer who conveniently amplified his patriotism when it served his views.

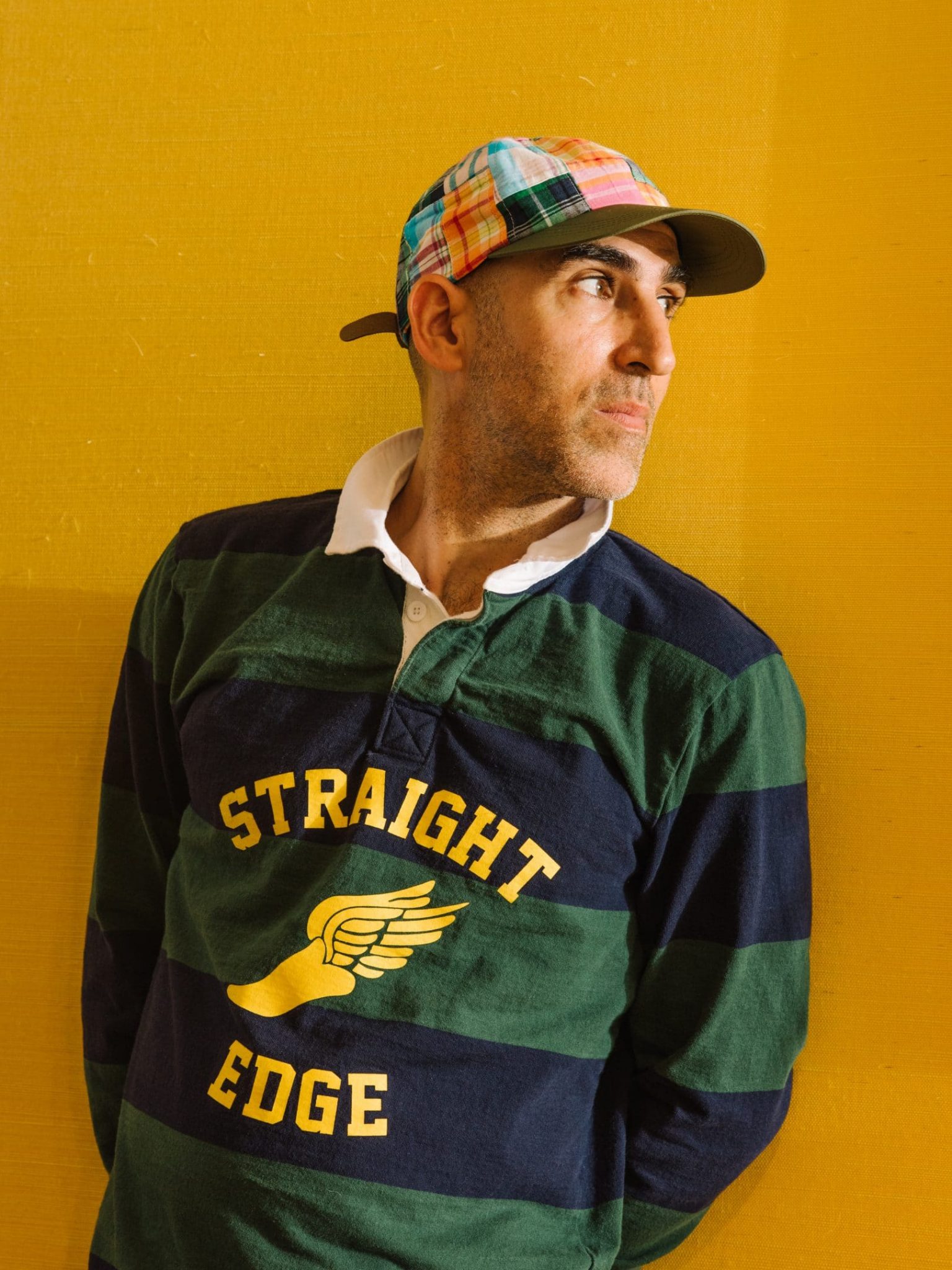

Babenzien is his own kind of complicated folk hero. He doesn’t have so much a biography as an oft-repeated, hype-propelling origin story—skating and surfing since age five, working in the skate apparel industry from age 13, deep ties with a murderer’s row of legendary brands like Pervert and Supreme. He’s lived a highlight reel of dopeness—all the right parties, people, places—during the three decade rise of New York’s street culture hegemony (“I’m like Forrest Gump,” he says, which somehow strikes me as an absurd understatement). His near decade-and-a-half as Supreme’s creative director cannot yet be given proper historical context but alone must quietly qualify him as one of the most influential minds in youth culture of the past 25 years. The man sneezes pure, uncut street cred.

Babenzien, who is 46, still deeply cares about skateboarding and surfing and punk and hip-hop. “I don’t surf nearly as much as I’d like to anymore, and that’s a real problem for me,” he tells me, unironically.

But he is also intensely concerned about the world and his place in it. Depleted natural resources. Plastic-choked oceans. Exploitative labor practices in manufacturing. Wasteful, mindless, addictive consumption. The American Dream marketed alongside regressive, rights-violating political policies. All with massive corporations and the ultra-wealthy pulling the billion-dollar strings while their shareholders cheer them on. It’s a horror show he compares, in no particular order, to a religious war, a variety of dystopian novels, and the movie Idiocracy. “People are just – not to pull any punches – people are just fucking dumb,” he says, pulling exactly zero punches. “People have just become really dumbed down and, to some degree, I think that’s by design.”

Meanwhile, the group with the power and influence to actually make a difference over a large time scale—young people—are distracted, waiting in line for streetwear drops, playing make-believe on social media, and just generally getting fooled into feeding the machine. “They think they’re being super punk and rebellious,” he says. “But, in fact, they’re just food for the rich because their money is just going up to the people that fucking hate them. And are creating laws to work against them. And are poisoning them.” The kids are going to hell in a hypebeast fit.

Babenzien’s theory of the world is not particularly unique or rare, even in the fashion industry. But in an era where many brands are eschewing integrity to chase a millennial laser pointer while others apologize publicly, his decision to weaponize his three-year-old brand Noah for the fight does seem admirably, if sadly, unique. He may not be opposing modern history’s greatest villains in Hitler like Guthrie was, but in a way he faces longer odds: he’s largely fighting the bad habits and behaviors of a world he had some hand in creating, and he’s fighting from the inside. While Babenzien is critical of society at large, his blast radius, of course, most profoundly impacts the space most closely connected to him. And while he proudly acknowledges his past work and the benefits it now affords him and his brand, he also suspects the pendulum has swung too far. “I don’t think we’re doing that culture that’s been building for 30 years any favors right now.”

And he’s taking action to help correct course. “You either say, ‘Well if that’s just the way the world [works] why should I even fucking care? I’m just going to get mine and do my thing and whatever because eventually it will flip and go back,’” he says. “Or you can take the position that when you are here, you should fight for your side and create as much good as you can.”

“To just be a clothing brand, to just make stuff and to just make money for a small group of people, was not going to be enough for me.”

This is actually Babenzien’s second crack at Noah after one failed attempt in the early 2000s. Though he returned to Supreme after, Noah was always percolating in the background. “It’s been 15 years or so of me thinking about if I did Noah again what would it be? How would it look? How would I use it?”

Babenzien finally resurrected Noah in 2015. The product retained some markers of its previous design aesthetic—elevated prep staples like rugby shirts and twill trousers with a nautical influence and youthful edge—crossed with a variety pack of other flavors: subversive graphic tees, surfing wetsuits, running gear, and occasional Italian suiting.

But the brand was also imbued with an invigorated, three-dimensional personality and a moral compass. This direction was brought into focus, in part, by the birth of his daughter, Sailor, in the year before the relaunch. “To just be a clothing brand, to just make stuff and to just make money for a small group of people, was not going to be enough for me,” he explains. “I wasn’t going to be able to look at my daughter and be like, ‘this is what we did.’”

He adds,“It is very much built into the DNA of the business that this company has to do good.”

Noah takes corporate good to its logical extreme, working to express it in all aspects of the business and brand. The company takes principled, specific stands on topics other companies would avoid. It helps that Babenzien only has a few, small, strategic investors, all of whom are fully onboard with his decision-making. He essentially has the freedom do whatever the hell he pleases, and he does.

“Brands are like celebrities. Like the brands themselves. If the brand has to behave a certain way to satisfy its audience—like, you have to be aware— that’s really weird,” observes Babenzien. “We don’t really do it. We have always said, ‘we do what we do.’”

As de rigueur policy, the company only works with carefully vetted, ethical factories who pay a living wage to workers (Noah product is primarily made in Canada, Portugal, Italy, and Japan, though the company does limited manufacturing in the U.S. and Honduras). They prioritize sustainable, natural fabrics that have longevity and, when possible, avoid using synthetic fabrics that leach plastic into the world’s water supplies. Naturally, this results in the most common rebuke they receive from customers: higher prices. But Babenzien wants to teach people that this is what “real” prices look like. “The price that’s based on somebody not being paid well, not eating well, not going to school, not having a nice home to live in—that’s a lie.”

On Noah’s blog and social media, the brand consistently discusses a variety of environmental concerns and is a frequent, vocal critic of our current presidential administration. The brand has made a regular habit of selling product to promote and raise money for a variety of causes: Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ rights, the Anti-Nazi League, and the recent border separations. And it puts its money where its mouth is in a variety of other ways. Babenzien notes, “We’ve gone so far as to say like, ‘look if you don’t like what we’re saying about Donald Trump, for example, then just send us your shit back, and we’ll give you your money.’”

Viewing Noah from the long shadow of Babenzien’s old employer neatly isolates the bet Babenzien is making on himself. Supreme, monolithic and unknowable, is brand identity by way of insouciant papal conclave. The devoted wait in frenzied anticipation for anonymous smoke puffs of product, personalities be damned. Noah, by contrast, is a firehose blasting Babenzien’s heart and mind to the world. It is selling the totality of Brendon Babenzien. “We do it in such a weird gumbo—it’s part skateboarding, part running, part politics, part environmentalism, music influence—all at the same time,” he says. “I’m just going to address all the things that are interesting to me, because I’m certain there’s other people who agree with one of those five elements if not more.”

With this many balls in the air, self-awareness is, of course, critical. “I always say—we can’t become this preachy [brand]. If we’re not putting out fun shit, too, and interesting graphics, and we’re not showing skating, then that would be death too. You’ve got to find that balance.”

If it all seems a little schizophrenic, it also comes off as genuinely so. One morning, Babenzien buzzed around the office skipping from topic to topic. He chatted about old skate videos. He explains how Noah’s refined aesthetic is an ironic palate cleanser as European luxury houses go full streetwear. He tried to conceptualize a needle-moving response to the NFL’s regressive anthem policy. He debated with his wife Estelle whether the plastic container from her subscription lunch service violates the rules of Noah’s “Plastic Free Week” (for the second straight year, the staff is attempting to go a week avoiding using any single-use plastics—cups, utensils, bowls, bags—to honor World Oceans Day). All in under 30 minutes and soundtracked by bouncy reggae.

Even as the business has grown—its team now has some 30 people—Babenzien is still largely responsible for all things Noah. “Right now, Brendon has his hands on everything still,” says Estelle, who designs the brand’s retail interiors. “He’s still writing blog posts and Instagrams. It’s great. We have obviously, like, now a great team that understand that mentality, but we don’t want to water that down.”

It’s enough to make you wonder if the clothing at this clothing company is a secondary matter. And the answer is that it’s not, but it sort of is.

Babenzien is careful to point out that Noah is, first and foremost, an apparel brand. But he makes an observation that many, all the way up to Yves Saint Laurent and Coco Chanel, have made in the past: there is a bright-line distinction between “fashion” and “style.” He’s called fashion “a disaster” in the past, and says it again to me. “Fashion is so funny. It’s like buying clothes and wearing clothes is your hobby. It’s so contrary to what I’ve grown up with because all styles sprung out of everything else.”

“We’re still trying to remind people that it’s the thing you do first,” he explains. “Personal style doesn’t require you necessarily to wear the latest thing. You just have an identity, strength, and will that comes through. It’s like how one guy can wear a white T-shirt and jeans and look like a fucking movie star and the next guy looks like a knucklehead.”

He adds, “Your personal style comes out of the things you do that give you life.”

Babenzien likes doing things. His staff at Noah all do a variety of things—they, too, skate and surf and run. One of the members of the design team is an avid birdwatcher and painter. An employee in their nearby store in Little Italy teaches yoga there on Wednesday mornings.

There is, certainly, some contradiction here. Babenzien himself readily admits that while Noah itself talks about surfing and skating and running, neither it nor its core customer are directly representing any one scene. Ironically, the scene Noah is in fact closest to is the streetwear fashion scene itself. “We exist in the hype cycle—there are definitely people buying our stuff because of the association culturally,” he acknowledges. But if buying a logo hoodie is an entree into learning about Noah’s other work, that’s fine. In a way, it’s by design. “The audience that really needs this information more than anyone is our community of people, who are arguably pretty vapid.”

He points out that Patagonia, an outspoken, action-oriented company he admires and seeks to emulate, is essentially preaching to the choir. “Rock climbers and fishermen and snowboarders don’t really need me to tell them what’s up,” he explains. “They’re already there. They already know this stuff. They spend time outdoors and they know that there’s a problem.”

All this “doing” is critical to Babenzien because he doesn’t think contemporary youth culture encourages doing much of anything. People are too busy creating the illusion they are busy. “It’s like, oh, let me be known for something, anything, and then I’ll get fame and glory and money. And if I have to create a style for myself that really isn’t based in any reality—like, I don’t skate or don’t do this and do that—that seems acceptable to some degree. People seem to be okay with that, or at least ignorant to the fact that it’s kind of whacked out,” he laments.

“I don’t fucking like that. It’s kind of the end of society.”

But he’s careful to zoom back out to the broader landscape. “When we talk about what we’re doing and the things I think should change in business, people think I’m directing it specifically at the culture I’ve come from, but I’m not,” he says with a chuckle. “I’m aiming it at the whole thing, including myself.”

“Everything we’re doing, we’re learning while we’re doing it. You know, there’s no claims of expertise here. It’s more like we have this vehicle and we’re going to try and do the right thing.”

Noah appears to be resonating. It has grown faster than initially expected. It’s logo has real cachet. “I was really pleased to see that some of those assumptions that were made are coming true. That was incredible.”

There are, of course, challenges. When I ask what responsibility he feels to sway his peers in the industry to adopt some of Noah’s business practices, he bristles a bit. “I would have to say that some of them just don’t give a fuck maybe about this, or even me. I don’t know,” he says. “Some I know absolutely do care and are happy that we’re out here doing this and are proud of the fact that they’ve worked with me or have known me.” He later adds, ”But, you know, specifically the people that I’ve worked with in the past and having an impact on them? You’d have to ask them.”

Predictably, there are also internet trolls who comment that Noah should just shut up and make clothes. But there is a a kernel of a good question here: if you are so concerned about the environment and buying habits, why even do apparel to begin with? Whether or not the fashion industry is the second or eighth most wasteful industry, its negative impact on the environment is undeniable. Babenzien here is clear—apparel is what they know and how they make their living. They are just trying to show a model for doing it better.

And while Noah welcomes feedback and dialogue—“if somebody has information that we don’t have, and they can share it with us and we can use it in the future, then that’s outstanding,” says Babenzien—they do have to deal with public suspicion and general misinformation, particularly when it comes to their prices. When the brand detailed specific products costs on its blog to provide transparency, a number of message board commenters lost their minds with accusation and speculation. “People start accusing you of all kinds of things, like you’re just getting a bigger profit, or you think you’re luxury, or this or that. So it’s hard to win. You just do the best you can.” (For what it’s worth, the pricing on those posts appears valid according to anonymous industry contacts)

Many of the other challenges Noah faces are due to size. In its environmental efforts, the company has tried to eliminate as much plastic as possible from its operations. But they still have to ship product from the manufacturer to their stores in polybags to protect it. They’ve tried a plant-based bag, but their quick expiration date made them impractical. And while recycled plastic bags exist, they are expensive enough to impact the price of the garment.

“Where we are today, it sounds like we’re literally developing our own post-consumer, recycled plastic bags,” he says resignedly. “The industry doesn’t care about what we want. They’re not coming up with reasonable solutions for companies like us to solve these problems. We’re not given many options. We’re still too small to really be impactful in changing the way bigger companies operate.”

When I ask why Noah doesn’t manufacture more of its product in the United States, and particularly in New York’s rapidly shrinking Garment District, size is again a primary factor (only Noah’s hats, which are assembled in LA, are regularly produced stateside). Noah just doesn’t have order sizes large enough to result in feasibly affordable prices. Another issue is the pure logistical headache of navigating the U.S. apparel manufacturing industry. Outside some mills in North Carolina and New England, the textile industry has been decimated by years of offshoring. Trims all have to come from overseas. And even once all the materials are gathered, very few factories in the U.S. are streamlined, full-service operations; in the Garment District, very often pattern-making, cutting, and sewing sit in different factories on different floors of different buildings. It’s a system that’s better suited to brands like Outlier, who source globally and then make tiny runs of experimental product in New York (their large orders are done in Portugal) or luxury brands like The Row or Rachel Comey, whose relatively steep price points can weather the cost.

When possible, Noah instead largely chooses to manufacture in a textile’s country of origin to keep costs lower and quality higher, which means Portugal, Italy, and Japan. “For us still today, we would rather put out a good product and have a few people be like, ’Oh I wish it was made in the USA.’ And when we can make it in the USA we will, when we get there. We’re just too small still.”

Size is, in the end, a central tension for Noah. Everything the brand does—the elevated “real” prices, the outspoken politics, the niche its product serve— seem, at first blush, to prevent the very scale needed to truly achieve its manifold goals. To be fair, though, Babenzien never imagined the business as some world-conquering cudgel anyway. “If we’re small, that’s fine, if our voice is heard,” he says.

Despite this, when he thinks about the future, Babenzien doesn’t see any limits to what Noah could be. “The goal for me would be to be around when this hype thing is gone—people are slowly returning to just being better consumers and buying stuff that they really love—and having a big enough audience in that space to support us, and hopefully become more powerful in a way so we can make even better products and more responsible products. And do more with the vehicle.” He suggests many ambitious directions the brand can go—new product categories, media, a record label. Estelle mentions a hotel concept. “There’s nothing stopping us from really doing anything,” Babenzien says.

In the meantime, they’ll keep fighting their fight. “Everything we’re doing, we’re learning while we’re doing it. You know, there’s no claims of expertise here. It’s more like we have this vehicle and we’re going to try and do the right thing. And each step of the way, we try and be a little better at it,” he offers. “But right now, we’re just doing our best.”

The odds are long, but not impossible. After all, cultural figures have a strange way of shaping the world in ways that surprise and stagger. Who would have predicted that Supreme and the streetwear industry it helped ignite would create all that it has: billion dollar valuations, inverting the fashion industry, setting the pace of youth culture globally. For his part, Woody Guthrie, just a man with a guitar, wasn’t ever going to be the sole cause of Allied victory in World War II. But the war was won. And his legend animated multiple generations of righteous protest in song across the American Songbook, the ragged voice that launched a thousand careers, from Bob Dylan to Joan Baez to Bruce Springsteen to Rage Against the Machine.

In 1944, a year before the war ended, Guthrie sat down in New York with his guitar to record dozens of songs in what would become a definitive anthology of his music. It included an old spiritual about life and consequence called “Sowing on the Mountain”. It closes with the following:

God gave Noah that rainbow sign

Sowing on the mountain, reaping in the valley

You’re gonna reap just what you sow

Sowing on the mountain, reaping in the valley

You’re gonna reap just what you sow